Hamad Butt was a young English artist when he died of AIDS in 1994. After graduating from Goldsmiths University in London in 1990, and a fellow student of artist Damien Hirst, he was a shooting star in the British art world. He was the subject of a long article in The Guardian newspaper in June 2023. It was to mark the entry of his works into the Tate Britain, one of England’s leading museums. That’s how I discovered him.

Today, academic researchers and art critics are working on his artworks. The research of art historian Dominic Johnson, Professor at Queen Mary University of London, has often focused on performance art and live art, generally from a “queer perspective”. In 2024, he will be developing a research project at the University of Southern California (Los Angeles), billed as ” the first scholarly study of the work of the British South Asian artist Hamad Butt, in the context of art and HIV/AIDS “.

In a parallel approach, I focus here, as a physicist, on a single piece by Hamad Butt, Cradle. It is represented below by an image of the artist himself.

https://hamadbutt.co.uk/familiars-part-3-cradle

A work that demands real presence.

First and foremost, I want to go to London to see this artwork, to be in its presence. In the photo, you can see its plasticity, its strength, its slightly mysterious immobility, its sheer mystery if Newton’s pendulum, chlorine and blown glass mean nothing to you. For it also imposes itself in “real presence” through the danger it represents, even if this danger is ultimately mostly potential, and certainly far less than those that accompany our everyday lives. But all the same, it’s there, staring you in the face.

Physics and chemistry are there.

Physics and chemistry are here in all their dimensions: the laboratory, research, but also as key elements in the development of a society largely based on the alliance between science, technology and industry in the 20th century. From this point of view, Hamad Butt’s work is extremely powerful: firstly, it stands before us with its magnificent and impressive plasticity, but also, and this is obvious to me, it is committed to showing how this society of the 20thèmecentury has deployed science and technology on a planetary scale, for everyone, and by taking responsibility for the induced risks, which can be significant. These are often part of the so-called major risks. The operation of industrial sites in Europe presenting a major risk is governed by the Seveso Directive. This directive was named after the Seveso chemical disaster in Lombardy, northern Italy. Dealing with major risks of industrial origin, and implementing protective measures, is not a matter for individual initiative here. At the heart of our “living together”, everyone must have confidence in the responsible authorities.

A Newton pendulum, chlorine, blown glass.

Hamad Butt’s work places physics and chemistry right before our eyes. In the case of physics, he does so by hijacking Newton’s pendulum. This device often uses five steel balls in contact at rest, which through their movement and shocks make obvious two fundamental conservation laws: that of mechanical energy and that of momentum. When the balls are thrown, their behavior is spectacular and the subject of countless online videos. In this way, the artist makes a very direct allusion to the fact that scientific knowledge and technological mastery have given us control and development over mechanized movement, and above all, speed! But Hamad Butt’s “Newton’s pendulum” doesn’t move. It must not move. It irresistibly evokes movement but setting it in motion is dangerous! The fragile glass spheres in this pendulum contain chlorine gas. A beautiful yellow gas… deadly if the dose is right. Three times six spheres full of chlorine!

Hamad Butt and the halogen series.

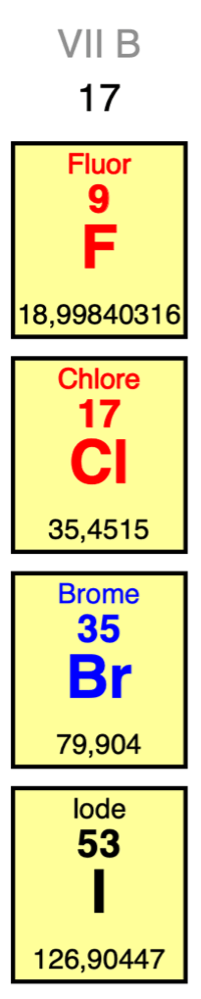

Chlorine is one of the chemical elements known as halogens. It is in the same column of the periodic table of chemical elements as fluorine, also widely used for its important applications, and probably even more dangerous to handle than chlorine. Hamad Butt didn’t venture into this field, as chemists must have advised him against it if he felt like it. Instead, he used the other 2 common elements in this column, bromine and iodine. Always with caution. In his triptych, group of three artpieces, entitled Familiars, Substance sublimation is based on the physico-chemical properties of iodine, while Hypostasis is based on those of bromine.

https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tableau_périodique_des_éléments#/

Chlorine, a dangerous and ubiquitous gas for its applications.

Chlorine is an extremely abundant chemical element. Sea salt, or any salt in kitchen, is half sodium and half chlorine, so to say … Bleach is one of the best-known forms of chlorine, especially for domestic use. In fact, chlorine has many important applications. The result is a major industrial activity! Given its hazardous nature, stringent and permanent industrial safety measures are unavoidable. A search using the key words “chlorine accident” shows that chlorine handling is highly regulated, and that failure to comply can lead to fatal accidents. In June 2022, an accident in the port of Aqaba in Jordan killed 13 people and injured over 250. A heavy container of chlorine was being loaded by a port crane, and the cable broke, sending it hurtling directly onto the ship’s deck. The dense yellow cloud that spread instantly left no room for doubt.

Youtube video: A chlorine leak kills 13 people in the Jordanian port of Aqaba

https://youtu.be/iRsJrwVMN8A?si=zRHbCmCbBKvN2NB7

The parallel with Hamad Butt’s Cradle is striking. The crane, suspension cables and chlorine tank are so close to one of the elements in Hamad Butt’s Cradle. The work, which predates this accident by a quarter of a century, is practically a miniature of the port’s facilities. Truly striking!

Hamad Butt reminds us of this pact: massive use at the cost of regular accidents.

The situation setting of the risk in this artwork, through the danger represented by chlorine gas, is supported by collaboration with chemists from Imperial College in London, and with a technician specializing in glassblowing. They have here established a unique relationship between arts and sciences, based on shared responsibility and a commitment to public safety. They all must ensure that the work does not pose a safety problem when it is exhibited to the public. For that, one needs to go into the details of the setup: the structure is stable, the wires are strong enough to last a long time, if not forever, and the glass spheres are perfectly watertight. This is what science, technology and industry have been doing everywhere for decades: producing a new device, an innovation, that is too interesting not to take on board the inherent risk and seek to ensure safety. But while Hamad Butt’s artwork is important, it is useless. It serves no purpose, has no practical use that would justify taking the risk. The difference here, then, is that Hamad Butt’s artwork, as important as it is useless, is a powerful reminder of the pact we all share. Clearly, we are willing to pay the price for accidents that are deadly and regular, but whose impact we find collectively limited enough not to do without innovation.

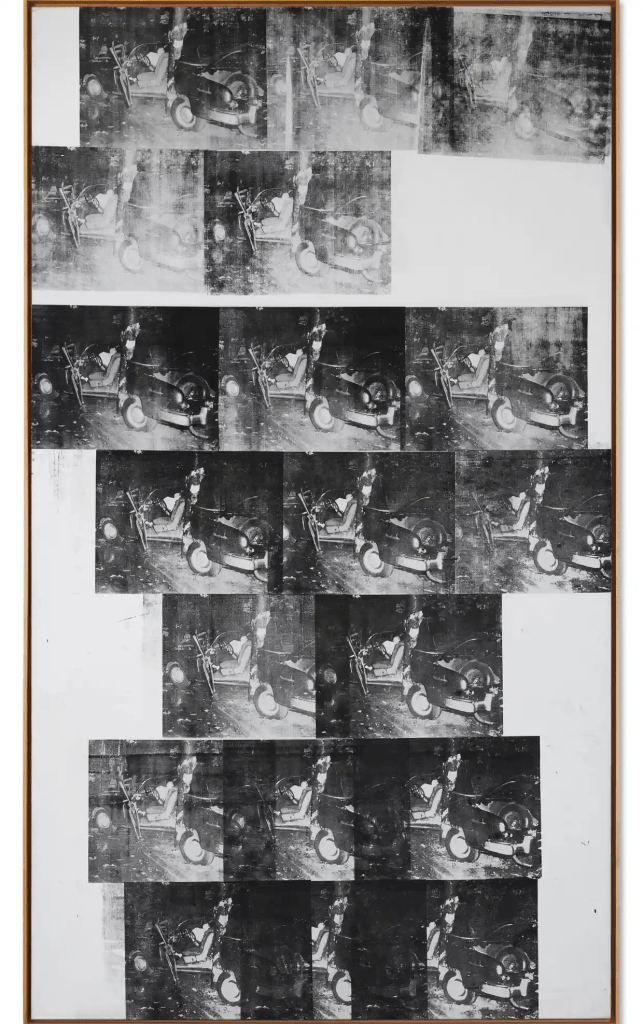

Andy Warhol and “The white car crash 19 times”

The most striking and terrible example of this pact is not chlorine. It’s motor vehicles, which are responsible for over a million deaths and tens of millions of injuries worldwide every year. This is the perspective behind Andy Warhol’s 1963 work “The white car crash 19 times”!

But with Andy Warhol’s work, there’s no risk to visitors other than on the road on their way home. The difference with Hamad Butt’s Cradle is crucial: the museum visitor is actually in the presence of chlorine gas. But every precaution has been taken. Although… the title of The Guardian’s recent article on Hamad Butt was:

‘Dicing with death’: the lethal, terrifying art of Hamad Butt – and the evacuation it once caused.

Cradle, a complex and multifaceted work.

On his retirement, Steve Ramsey, the glassblower, who was then in a scientific research laboratory at Imperial College, recounted his collaboration with Hamad Butt:

I worked for over 2-3 years with this artist, and he kept disappearing, even though he was pressurizing to get this piece made. I found that quite frustrating, but I didn’t know he was actually dying of AIDS. He was only 32 when he died.

To perhaps open up another approach to Hamad Butt’s work, one could, for example, watch French film of Robin Campillo “120 Battements par minute”, released in 2017, and/or follow Dominic Johnson’s work on Hamad Butt. To me, the different paths of discovery of these works are indissociable, even deliberately intertwined by Hamad Butt in Cradle. This is why I wrote this article and why I find Hamad Butt an amazing artist. Indeed, with works that impose their real presence on visitors, and generate such different but powerful questions, Hamad Butt remains in our lives.