Currently on view at the Bourse de Commerce/Collection Pinault, the exhibition “Arte Povera” traces the Italian birth, development and international legacy of this singular artistic movement. Over 250 works by the main protagonists of Arte Povera are on display.

Title image : Pier Paolo Calzolari, Untitled (Mattress), 1970. ADAGP, Paris 2024 Private collection, Lisbon. View of the exhibition “Arte Povera”, Bourse de Commerce – Pinault Collection, Paris, 2024 © Photo : Florent Michel / 11h45 / Pinault Collection

This is an immediately impressive exhibition, not only in terms of the space in which it unfolds and the 250 works presented, but also in terms of the nature of the works, most of which were conceived in Italy, at the heart of the “trente glorieuses”. Fossil fuel energy is explicitly at work, transforming matter in a myriad of ways. Energy, materials, transformations: the physicist is in his element!

Young Italian artists at the birth of Arte Povera

In 1967, when art critic Germano Celant created this movement, calling it “Arte povera”, Michelangelo Pistoletto was 34, Giovanni Anselmo 33, Jannis Kounellis 31, as was Luciano Fabro. As a physicist, I realize during the visit that, while my discipline helped transform the world in this period, it is not a benchmark here.

These artists’ proposals are rooted not in science, but in their own creativity and vision, against a backdrop of studio experimentation. They go behind the curtain, showing the heart of the machine without the design. This brings to mind the opposition between their contemporary visions, with Ray mond Loewy on the one hand, the designer of the entire consumer society – already in 1893, the Chicago World’s Fair announced “Science Finds, Industry Applies, Man Conforms”) – and designer Victor Papanek on the other, who in 19 7 1 wrote Design for the Real World, Human Ecology and Social Change.

Working outside the scientific and technical conceptual framework at work all around them, they seize upon it only to turn away from it. They use everything from materials and devices to the thermal machines that shaped the twentieth century (power plants, cars, airplanes, etc.). By exposing everything, they show us the world as it is and as it will become, increasingly industrial and energy-hungry. Their lucidity and relevance are formidable.

Emblematic works

Michelangelo Pistoletto’s “Mirror Paintings” are above all stainless steel plates. Pistoletto had also tested aluminum: steel and aluminum are two of the leading materials of the thermo- industrial society, and require – an apparent paradox for a “poor art” – a very high level of scientific and technological mastery, as well as a great deal of energy to produce.

Michelangelo Pistoletto invites us to look ourselves in the face in the material that, at that very moment, was changing the world, in the age of triumphant steelmaking. What a mise en abîme!

Jannis Kounelis burns gas through a nozzle in a raw steel flower. The gas forms a small blue flare, producing a characteristic noise. The gas cylinder is clearly visible. It’s a very clean, very controlled fire, one that will enable us to reach high temperatures, and thus produce movement and transformations in matter.

Jannis Kounellis, Untitled (Margherita di fuoco), 1967. Nicolas Brasseur/Pinault Collection

But let’s stop for a moment to consider Gilberto Zorio’s Piombi II (1968). It’s best described in the exhibition label:

“Two sheets of lead, copper sulfate, hydrochloric acid, fluorescein, copper braid, rope. The work, conceived as a battery, transforms chemical energy into electricity. On the floor, Gilberto Zorio places two lead containers attached to the wall by a rope, and pours into one of them a mixture of copper sulfate and water, which turns blue, and into the other a mixture of hydrochloric acid and water, which turns green. A braided leather thread is stretched between the two containers, immersed at each end in one of the two liquids. In prolonged contact with the two substances, the copper is covered with crystals, while the coloring of the two liquids reflects the transmission of energy from one to the other. The artist uses industrial materials to create an energetic process that evokes an alchemical experience.“

The work is rustic, resembling a shoddy laboratory set-up. We are placed at the heart of the device, as if the artist were lifting the hood. And with this work, the detailed review of the key elements of 20th-century industry continues: in this case, electrochemistry and electrometallurgy.

Other striking works include the thermal machines by the same Gilberto Zorio. What a shock to see them like this! They punctuate the entire exhibition, from the entrance to the rotunda. You can also see them in a room dedicated to them (the “Casa ideale”), where you can feel the cold! The motors and heat exchangers are on display, part of the work. We can see them wasting energy live, trying to cool the world. Like the air-conditioning units in stores that are wide open to the outside world… Here, the cooling is such that frost forms on the lead structures, as in a refrigerator whose door has been left open. Having seen the exhibition on its opening day, I’m not sure whether the aim is to let the frost accumulate in an ever-thicker layer.

I’m thinking here of Sadi Carnot’s unique and major work, Réflexions sur la puissance motrice du feu et sur les machines propres à développer cette puissance :

“If some day the improvements of the fire engine extend far enough to make it inexpensive in establishment and fuel, it will combine all the desirable qualities, and cause the industrial arts to take off in a way whose full extent it would be difficult to foresee. Not only, indeed, will a powerful and convenient engine, which can be procured or transported everywhere, take the place of engines alreadỳà in use, but it will cause the arts in which it is applied to take rapid extension, it may even create entirely new arts.”

Carnot was a visionary when he formulated this as early as 1824. But so was Gilberto Zorio, who, like his comrades, took the measure of the subject, and continues to confront us with the effects of thermo-industrial civilization.

Today, artist JR asks again: “Can art change the world?” Back in the 1960s, Arte Povera strongly emphasized that art could show how the world was undergoing a transformation on an unprecedented scale. This group of artists had identified all the elements: the massive mobilization of energy, the profusion of materials used and the ever-expanding industrial transformations. They created works without artifice, “poor” in this sense, stripped of the layer of design then in place to make everything functional but also desirable. Here, the fridges are naked, without the metal cladding of the mythical American Coldspot refrigerator created by Raymond Loewy and symbolizing the “American way of life”. If you think back to contemporary Arte Povera advertisements or American films, the contrast is stark.

Materials everywhere Materials everywhere

Arte Povera artists have explored almost everything. In Venere degli stracci (Venus of the Rags), Michelangelo Pistoletto displays a mountain of fabric and clothing piled up in front of a statue of Venus. As we know today, fabrics, clothing and fashion represent a global industry that consumes huge amounts of resources and generates enormous pollution.

Michelangelo Pistoletto, Venere degli stracci, 1967,

Further on, Jannis Kounelis exhibits a pile of coal. But other artists also make use of materials: we see leather, stone, cement prefabs, water of course, fabrics, woven copper wires and so on. Finally, there are the works of Giovanni Anselmo, in a room that stuns the physicist in me: our smartphones carry sensors that precisely measure orientation in space, vertical line and gravity, horizontal plane and rotation in space. The artist, following a singular path that I can’t even imagine, inscribes this evidence through installations and sculptures of moving elegance and simplicity.

Giuseppe Penone, another world?

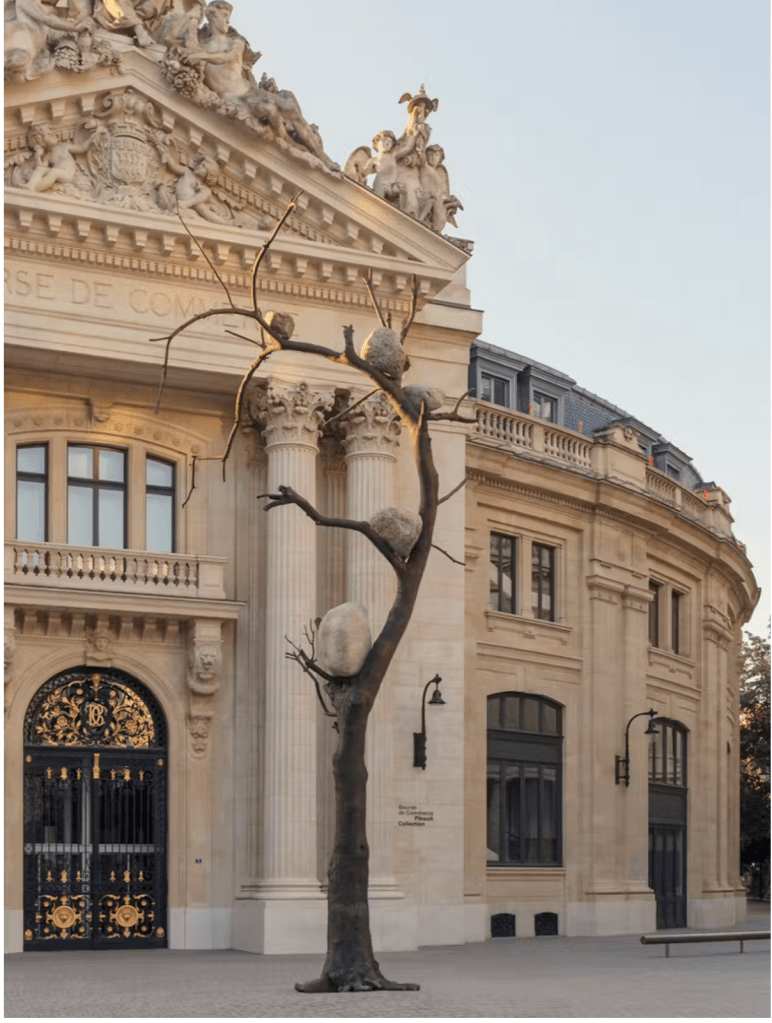

I discovered Arte Povera long after I became acquainted with the work of Giuseppe Penone. He’s been taking my breath away (and sculpting it, too) for a long time now. Here, his metal tree loaded with heavy stones in front of the Bourse de Commerce opens the ball. I’ve already written about some of his works, always as a physicist, which is in no way a reference for him. I collaborated with him on Essere vento, and sculpted for him the grains of sand exhibited here. In Arte Povera, he has carved a singular furrow, which seems to me to open up other horizons and raise other questions.

View of the forecourt of the Bourse de Commerce. Romain Laprade/Pinault Collection

This article is a translation of article original which was first published in The Conversation under Creative Commons licence.