Humanity embraced photography, and it enriched human relationships—the very core of our humanity. The transformation of the world through this technology has been emancipatory. And what about today?

As for today, is this movie a final look back before the battle for the future?

Transitions—we are already in them. Climate, biodiversity, and technology. Faced with this future that is, at the very least, uncertain, if not threatening, Cédric Klapisch’s film takes us about 150 years back. In this story, photography in its infancy already appears as family album pictures and framed portraits on dining room sideboards. This film offers a final backward glance before the unknown of the irreversible transitions now underway.

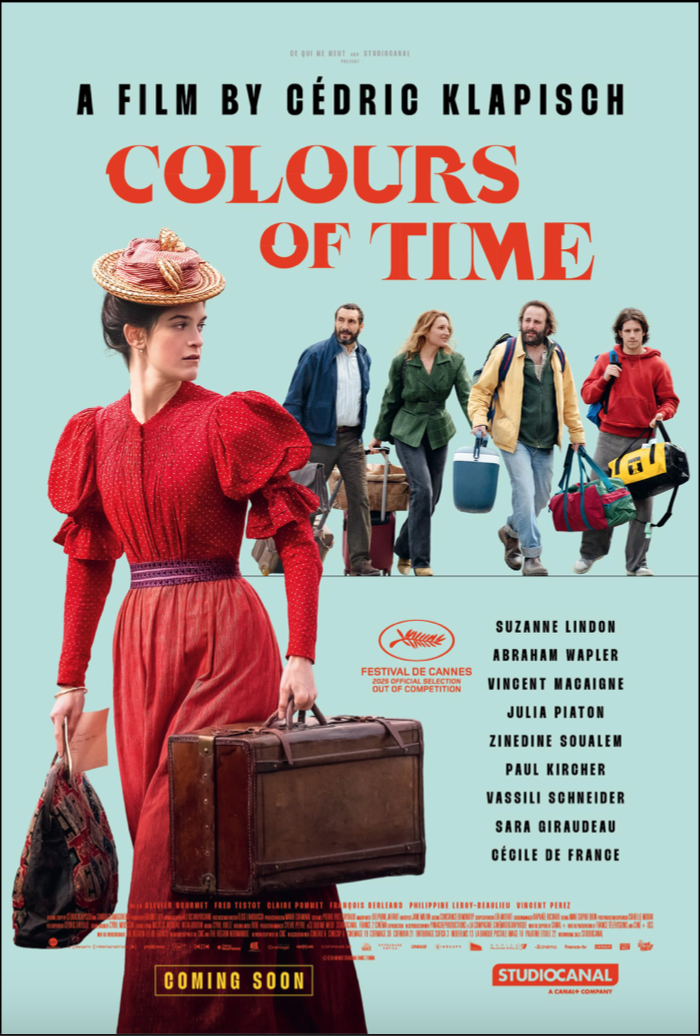

Colours of Time – Official Trailer – Cédric Klapisch (2025)

First of all, the film sets forth a thesis. At every moment, throughout its entirety.

By 1890, photography—first invented in 1840—was beginning to spread across the world. Probably the first technology to do so to this extent and at such speed, it would, in the span of just two or three generations, profoundly transform family, friendship, indeed all human relationships. Yet from the very start of its rise, this transformation was the result of popular appropriation. The place of photographs—whether in family albums or framed on sideboards—was determined by everyone for themselves. This technology did not emerge as an instrument for manipulating humanity, unlike today’s Tech, which all but explicitly captures attention.

In his 2024 film Eddington, Ari Aster explores the violent dehumanization at work in social networks, smartphones, and AI. In Klapisch’s film, if photography transforms human relationships—across generations too—the result appears as an opening toward new interactions between people, leading to an intensification of family, friendly, and social ties. By contrast, the vision of our future in the Klapisch movie does not indicate such renewal, but rather the mobilization of family, education, writing, and art in order to engage in the battle against technologies that threaten these relationships. In this respect, Ari Aster’s and Cédric Klapisch’s films are not so far apart. Cédric Klapisch wants to leave us a chance. Ari Aster does not…

Photography. Across time, across space.

To build this thesis, the filmmaker proceeds by successive touches, somewhat like Impressionism in painting—an important element of the story itself.

Two periods alternate in the film. Our own, today’s world of digital technology, smartphones, social networks, and rapidly advancing AI. And France around 1890, where a major change was underway: the development of photography. Invented half a century earlier, it was already widespread, yet still largely the domain of professionals such as French actor Fred Testot, who plays Félix Nadar, the star photographer of the time, and the young photographer played by Vassili Schneider. Of course, we know the outcome in 2025: everyone takes photos. In his closing credits, Klapisch runs through nearly a century and a half with dozens of photographs taken with a multitude of different devices. These photographic journeys tell lives and stories just as people do at weddings, retirements, and funerals… you need to stay in the theatre after the film ends.

And photography changes everything

Klapisch situates the action 50 years after photography invention, before its worldwide explosion. But in 1890, the game is already over. Photography is bound to change everything. For me, the film revolves around this single idea. As the young photographer remarks, this technology is, in essence, a simple chemical recording of light reflected by the real world onto a photosensitive surface. It is on this two-dimensional sensor that optical control, through lenses and mirrors, forms what physics calls a “real image.” The technology of this apparatus continues to evolve even today, but the result was already stunning in 1840. Photography changed everything about the image, on a massive scale—and it evolved in an extremely short time. At every level: the accuracy and resolution of the image, its production, its distribution, and thus its ubiquity. The film strongly emphasizes that photography is, above all, what people have made of it since its invention. Its definition, its place, its role—these are the results of collective appropriation.

Synthetic images—those created without a camera, generated by AI—open up a radically different era. In this respect, one should note the remarkable work of the young artist Martyna Marciniak. The film alludes to it in passing: the yellow of a dress clashes in a photograph taken before Monet’s Water Lilies at Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris, and someone remarks that it would be easy to alter the colours of Monet’s painting later by digital processing. The issue of appropriation, of the control of people’s minds and bodies through images, now arises in entirely new terms. A period lasting 150 years has closed.

The whole film follows this exploration of photography’s arrival

This thesis on photography’s place and its popular appropriation structures the entire film. It consists of a multitude of short scenes, often just sketched out, but in the age of TV series the viewer fills them in instantly. Thus, Vincent Macaigne’s character snatches Julia Piaton’s smartphone from her hands to free her from a screen that traps her in an endless breakup. And that’s it. It’s quick, but the message is clear. After the camera comes the smartphone. Twenty years after entering our pockets, its popular use does not really allow us to discern positive forms of appropriation that could prevent large-scale psychological manipulation of attention. Klapisch is not optimistic about the technologies of the twenty-first century. In Eddington, Ari Aster is outright bleak.

Painting, magic, and writing surround photography

These three elements intertwine with photography to form the structure of the film. Along the way, one remains impressed by the sophistication of the script and narration. I regret being unable to pinpoint exactly how this sophistication is achieved through the film’s shot breakdown and editing. I can only sense the effort.

Impressionism: painting in the age of photography?

Claude Monet is a central character in the film, as is his painting Impression, Sunrise. Between painting and photography, Klapisch’s message is clear, and in fact rather conventional. After photography, painting seems obsolete—its relevance fades compared with the precision, resolution, and power of photography in front of reality. This is, in essence, what the young photographer played by French actor Vassili Schneider boldly asserts. His friend, a young painter played by French actor Paul Kircher, replies: painting is elsewhere, its place in humanity lies elsewhere. And indeed, following the painter into that “elsewhere” compels us, as prominent French art historian Georges Didi-Huberman says, to reinvent our language in order to stand together before the canvas. Here, French actress Cécile de France plays an art historian, truer than life, who radically reinvents her language—otherwise so sophisticated. Projected into 1870 through hallucinations induced by ayahuasca, the shamanic potion of Amazonia, she encounters the critic Louis Leroy, who coined the term “Impressionism.” Unable to bear his comments on Monet painting, she punches him in the face. That, perhaps, is the force of painting…

Magic

Magic surges in the movie. It projects nowadays people in1870. This sudden arrival of magic and this time collision surprised me. Yet this plays an important role in the movie. For one, it propels the film forward in a leap, which was likely fascinating already in the screenplay stage. Beyond that, it takes us deep into a distant past, long before photography, even before writing, when humanity created myths, religions, and thus magic, thereby building societies. Vincent Macaigne’s character, addicted to shamanism, leads everybody to an ayahuasca experience. The subsequent sleep filled with hallucinations proves a highly effective medium for time travel and the collision of eras. Here, Klapisch revives magic, emerging from the dawn of time to stand against technologies that invade and transform human relationships. The question of the relation of magic to reality is not the point. French actor Zinedine Soualem, playing an elderly teacher dismisses the issue in a brief line. This teacher in XXIth century is reminiscent of the famous teachers in French elementary schools in beginning of XXth century. They were nicknamed “hussards noirs de la République”, hussards were famous soldiers of French army. These teachers championed an education based on rationality, laicity and put any religion at distance of French school. Anyway, that magic is solely based on imagination and hallucination is clearly not the subject here. By invoking magic, the film roots itself in humanity’s long history: how to be together, how to be a family, how to be friends, how to meet? Probably by telling stories that become deep, shared perspectives on existence, on absence, on the passage of time, on death. After magic and writing, photography in its turn transforms these fundamental, age-old questions.

Writing

The thread of writing woven through the film is beautiful, introduced in fleeting touches. Writing appears first: Suzanne Lindon’s character tells her fiancé that she will send him letters. It is 1890 in the Normandy countryside. He replies that she cannot read or write. But she is determined to learn. By the film’s end we learn she will become a schoolteacher in the early twentieth century. Elsewhere, we see a village schoolteacher writing in the nineteenth century. The beauty of her calligraphy—with inkwell, penholder, and nib—brings tears, especially for viewers over sixty, like Klapisch himself, or me (the ballpoint pen were finally authorized in French school in 1965). Close to movie end, the French teacher’s retirement in 2025 is a memorable scene. Such moments of gratitude exist in France more often than one might think. The figure of the teacher still carries great weight for many, despite deep transformations taking place in French school system. And then, especially In France, how better to invoke writing, transformative force of the world, than with French actor François Berléand, mischievously portraying a flirtatious Victor Hugo who doubts nothing? That’s Hugo all right. A hilarious minute.

Conclusion

Colours of Time, in its 1890 episodes, begins with magic, leans on eternal, universal painting—that is, art—and passes through writing, underlining the central role of education, in order to explore the revolution of photography. Cinema would follow, its birth evoked in mere seconds. The film runs straight from 1870 to today. The dramas of history are acknowledged in passing, but one must catch the references quickly. It is a thesis, not a historical fresco covering 150 years. And the film’s thesis is that this time, the world’s transformation by technology was emancipatory, that humanity embraced writing and photography to enrich the human relationships that constitute our humanity.

When it comes to the twenty-first century, the tone shifts. One feels anxiety, apprehension in front of what is coming—the new “arrival of the future”, following the French title “the arrival of the future.” Tech asserts itself and, to date, seems capable of preventing any new appropriation that might foster novel ways of being together, perhaps by subverting it. Instead, it undermines the very foundations of our humanity. The film is not necessarily pessimistic here. It seems rather to stage the prospect of an immense coming battle. With lightness, fragility, and childlike naivety, Vincent Macaigne’s beekeeper character—familiar to us all—appears as the commanding general leading the charge…

The contrast with Ari Aster’s vision is stark. His outlook is pitch-black. The battle is lost.

EDDINGTON – Trailer

In his interview with the French newspaper Le Monde on 19 July 2025, Aster declared: “I think we all live in different realities today. No one agrees anymore on what is real. I wanted to make a film about what it means to live in a world where people can no longer agree on reality, and what happens when they end up in conflict.” Psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan once said: “The real is what one bumps into.” Physicists could even cosign this definition—without hesitation, though at the risk of misunderstanding. No matter: the encounter is striking. And photography reinforced our link to a single, shared real—to the real itself. Not so with social networks and synthetic images.